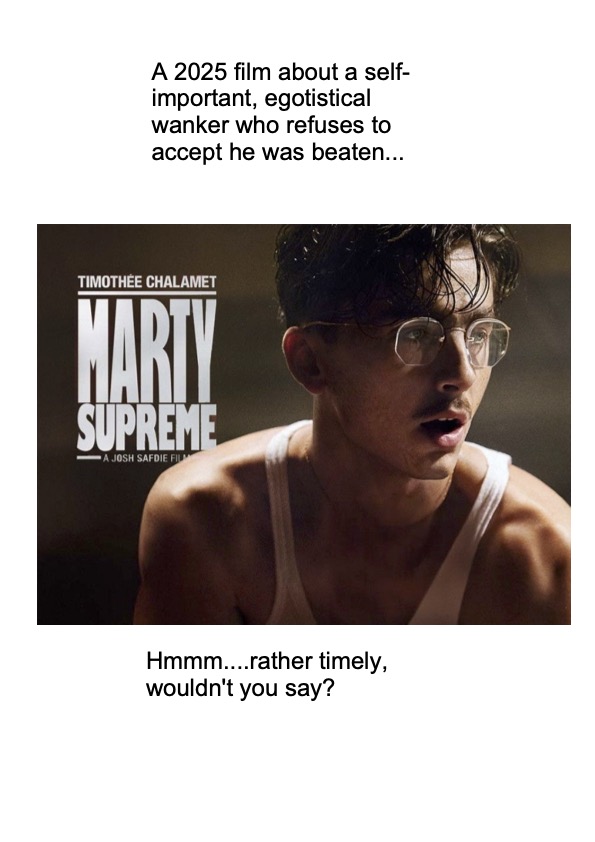

I went with John to watch Marty Supreme on Thursday evening. It’s a very odd film – a biopic set around a central character who I left the cinema despising.

The guy was so obnoxious, arrogant and cocky that I left the cinema wondering whether the audience was supposed to have any kind of sympathy with him, or why anyone would make a film about such a jerk. But then it struck me that the film was just a very timely allegory for Donald Trump, or even the USA itself.

Marty Supremeâ Review: Timothée Chalamet Sprints to the Top

The actor stars as a magnetic, striving table-tennis champ in Josh Safdieâs new movie, one of the most exciting movies of the year.

By Manohla Dargis

Published Dec. 24, 2025Updated Dec. 25, 2025

Marty Mauser, the irrepressible hero of Josh Safdieâs electrifying new movie, is rocketing toward his American dream at the speed of sound, running and racing while working every conceivable angle. Itâs 1952 New York, and Marty â played with ferocious verve and pinwheeling arms by Timothée Chalamet â is a table-tennis shark and aspiring world champion. Heâs a classic striver ping-ponging between worlds and loyalties, between the ties that bind and a complex freedom, between community and self. His horizons seem within reach, but because life for Marty is one hurdle after another itâs also one hustle after another.

A hyper-charged take on a bildungsroman, âMarty Supremeâ is one of the most thoroughly pleasurable American movies of the year and one of the most exciting. Part of what makes it electric is how organically its numerous parts â its themes, characters, camera movements and accelerated pacing â fit together in a whirring whole. The film touches on big, weighty subjects like Jewish identity, family, community, class, assimilation and success, but it isnât didactic and doesnât serve up any life lessons, in the pious finger-wagging manner of many American independent movies. Its ideas are one with its realism, with its many layers, lush textures, anarchic furor, squalid apartments, jampacked streets and tenacious, pulsing life.

Thereâs plenty to chew over, but Safdie is as much a natural entertainer as a born filmmaker (not every director is both): He wants to grab hold of you, and once he does, he doesnât let go. (His earlier features include âUncut Gems,â directed with his brother, Benny.) Heâs got an ideal hook in Chalametâs Marty, a charmer-schemer whose ambition fuels the story and takes him from the good, old Lower East Side to points across the globe. Heâs a sensational character (inspired by a real tennis-table champ, Marty Reisman) in a film crammed with the kind of vivid personalities and unhomogenized faces â creased, lopsided, beautiful â whose singularity is being increasingly expunged from American mainstream entertainment.

Marty is working in a cramped shoe store when the story opens, trying and failing to squeeze a female customerâs substantial foot into a daintier selection. Itâs the first of a series of setbacks for Marty, who almost immediately fobs the customer onto another clerk so he can service his married girlfriend, Rachel (the charismatic Odessa AâZion), in the backroom. Within minutes of zipping up, Marty is hurdling toward his future. He tries to persuade his boss to bankroll a venture, pulls out a gun, commits a crime, flees the apartment that he shares with his mother (Fran Drescher) and flies to London, where he meets a new romantic interest, Kay (a terrific Gwyneth Paltrow), a bitterly married ex-Hollywood star.

Safdie and his co-writer, his longtime collaborator Ronald Bronstein, keep Marty busy with dreams and schemes â he wants to create a signature line of orange table-tennis balls â and knotty personal entanglements. Marty is angling to become a world champion, a single-minded goal that creates a strong narrative through-line that regularly spins off into comically frenzied, at times brutal detours. Safdie is very good at orchestrating chaos, and while he often plays these interludes â with their leering faces and thrashing bodies â for horrified laughs, they also create a mounting, anxious sense of instability. At any moment, something can go wrong and often does, knocking people off course and worlds off their axes.

Yet Marty has remarkable staying power, and for all his misadventures and the spasms of convulsive violence that he hurdles over, he rarely falters. His drive is one reason, even if from the start itâs clear that he has support from people in his life, including Rachel and his pal, Wally (Tyler Okonma a.k.a. Tyler, the Creator), another player who Marty periodically teams up with to relieve suckers of their cash. Martyâs relationship with his mother is, by contrast, inexplicably combative to the point of hostility; his father is M.I.A. Whatever else he is, Marty isnât the stereotype of a mamaâs boy â that noxious, sexist cliché of the putatively effete, emasculated Jewish man. Marty is an athlete and a tough, streetwise New Yorker.

The city is one of the filmâs triumphs, a Lost New York that Safdie, with his crew (Jack Fisk is the production designer), has beautifully reimagined and populated with a vivid supporting cast (Sandra Bernhard and a volcanic Abel Ferrara, among others). Itâs here, amid unreconstructed tenement apartments â with their shared toilets in the stairwells and archaeological layers of paint â and among cluttered downtown stores and mysterious, dimly lit table-tennis parlors, that Marty came to be. Thereâs a romance and danger here, and movie love, too. Ken Jacobsâs great 1955 nonfiction film âOrchard Streetâ is one inspiration. The influence of Martin Scorseseâs 1973 âMean Streetsâ is just as conspicuous, and thereâs more than a hint of Johnny Boy, Robert DeNiroâs character from that film, in Martyâs swagger.

Gently deglamorized, his face a moonscape of zits and scars, Chalamet inhabits Marty fully with quicksilver emotional changes, a physically grounded performance and, crucially, a deep-veined vulnerability. Marty can be cruel, carelessly or not, but the expansiveness of his sensitivities is an argument in his favor. Heâs especially unkind to Rachel, a childhood friend whose love he sees as a trap. (He tells her in one fraught exchange that while he has a purpose, she doesnât.) Kay, by stark contrast, is a glamorous emissary from another world. They catch each otherâs eye in London and, before long, Kay is sneaking out of the hotel suite sheâs sharing with her husband (Kevin OâLeary) and slipping out of her fur in Martyâs rooms.

Kayâs entrance complicates both Martyâs life and the story, putting into dramatic form the tension between his explicitly Jewish world and the larger, at times aggressively hostile non-Jewish world. The filmmakers donât often overtly reference Martyâs Jewish identity; itâs a given, like the Lower East Side air he breathes. On the foreign land of London, however, his identity is foregrounded in a series of scenes, by turns squirmy and wildly strange, that include one in which Marty makes a shocking joke about Auschwitz to some reporters. âItâs all right,â he laughs. âIâm Jewish, I can say that.â He then announces that heâs Hitlerâs worst nightmare. âLook at me,â Marty says. âIâm here,â which is as self-serving as it is poignant.

This moment sets up the most haunting and meaningful section in the film that, in several brisk, freighted scenes â including a flashback centered on a startlingly surreal Holocaust survival story â briefly scramble the timeline and firmly bridge the near-past with the present. (A similar sense of historical continuity is created on the soundtrack, which includes Oneohtrix Point Neverâs synthesized score, blasts of 1980s pop â Tears for Fears, etc. â as well as period and classical music.) At that point, the world seems like Martyâs oyster. Heâs come to compete in the British Tennis Table Open and will soon play the Japanese ace, Koto Endo (Koto Kawaguchi, a real championship player). Marty is at the top of his game, with a strong attack and the burning confidence that draws others to him even as it also singes them.

After seeing the film the first time, I flashed on Budd Schulbergâs 1941 novel âWhat Makes Sammy Run?,â whose tragic title character (a âfrantic marathonerâ) lays others to waste on his mercenary climb to the top. For all their respective mileage, though, Marty is Sammyâs stark antithesis. Marty has drives and desires, yet his course isnât that of the classic bootstrapping American individual. Marty has family and he has friends (however fraught), and he has the buzzing Lower East Side, that glorious hive of immigrant aspirations, struggles and victories. Like Marty, Sammy sprung from there, as well as from America. Yet Marty, even during his darkest, most solitary moments, is also cradled by other people and by love. He is Hitlerâs worst nightmare: Marty is here and he is hungrily, blissfully alive.

Review generally positive. Oscar buzz for Chalamet

LikeLike